The

Near Heights contains many identifiable neighborhoods - Nob Hill, Ridgecrest,

University Heights, La Mesa, Trumbull, Victory Hills, Silver Hills, the Kirtland

neighborhood. These neighborhoods and the commercial areas, parks, and institutions

that serve them are some of the most recognized in the city.

The

Near Heights contains many identifiable neighborhoods - Nob Hill, Ridgecrest,

University Heights, La Mesa, Trumbull, Victory Hills, Silver Hills, the Kirtland

neighborhood. These neighborhoods and the commercial areas, parks, and institutions

that serve them are some of the most recognized in the city.

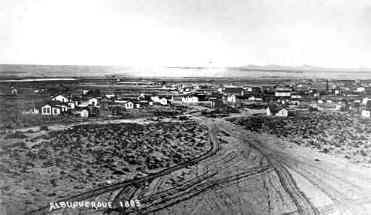

The historical development of the varied neighborhoods surrounding the campus of the University of New Mexico (UNM) provides a rich case study of the shifting cultural geography of 20th-century Albuquerque's built environment. At its inception in the early 1890s, UNM appeared as a solitary, three-story brick sentinel, poised on the empty east mesa above the bustling new railroad town. As late as 1910, after a decade that saw Albuquerque's population practically double from 6,335 to 11,020, fewer than two dozen houses stood east of the steep sand hills that rose sharply where Interstate 25 now separates the downtown area from the Near Heights. There, contiguous to Huning Highlands, wholesale grocer and visionary real estate developer Martin P. Stamm purchased land in 1891 east of the city limit at High Street and platted the Terrace Addition stretching four blocks south of Central Avenue all the way to Yale Avenue.

|

Kenneth Balcomb, in A Boy's Albuquerque, recounted that the town's consensus at the turn of the century was that Stamm "was 'way out' in trying to develop that area . . . considering that it took an hour with horse and buggy to struggle through the sandy streets he had scraped out to get to his headquarters." Indeed, after almost two decades of development, only fourteen houses had been built in Stamm's addition. And further east, only eight houses had been built by 1910 in the new University Heights subdivision that Mayor Daniel K. Boone Sellars, Harvey B. Fergusson, and others had platted four years earlier. They were banking on an early extension of the city trolley system to their new suburb. Grandly advertising their $25 to $275 lots between Central and Garfield, Yale, and Girard as "The Coming Aristocratic Residence Section of Albuquerque," the optimistic boosters of the Heights challenged the then primary north-south transportation axis of the town.

In its early decades, new Albuquerque's commercial and residential growth had been clearly defined by the grid laid out adjacent to the Santa Fe Railroad, with principal growth west of the tracks in a north-south orientation. The coming of the automobile at first merely underscored this familiar pattern: the fastest growing sections of town between 1910 and 1930 were those areas near U.S. Highway 85 along North and South Fourth Street.

The prevalent north-south development would prove short lived. The change began when six and a half square miles of empty east mesa south of Constitution all the way to San Pedro, thereby practically tripling the territory of the city. The mobility made possible by wide ownership of the automobile also began to realize its fragmenting potential. As the general population rose 75% in the twenties - from 15,157 to 26,500 - Martin Stamm's vision of a significant suburb in the Terrace Addition seemed about to come true. New developments spread north of Central, including what was first known as the Country Club Addition (now Spruce Park) between Grand and Las Lomas. Thus the number of houses rose from about 175 in 1920 to 760 in 1930, a 330% increase. University Heights also began to fill rapidly with over 300 new dwellings erected in that decade.

|

Just as optimistic was the initial platting and construction of over 100 houses by the Monte Vista Development Corporation between Girard and Carlisle, north of Central. East of Monte Vista, other additions lay platted but barely developed: College View, Burton Park, Parkland Hills, and Ridgecrest. While not exactly a set of "aristocratic" neighborhoods, the new residential areas surrounding the university were primarily composed of upwardly mobile, middle class residents--white-collar salesmen, skilled foremen, teachers, and owners and managers of small businesses. Albuquerque's mayor, Clyde Tingley, for example, moved with his wife, Carrie, into that area of Stamm's addition now known as the Silver Hill neighborhood. Large numbers of substantial brick homes and wood frame, California-style bungalow, "Anglo-American Homes," as a 1930 advertisement proclaimed, vied with frame-stucco variations of the modified pueblo revival houses increasingly common throughout the city. Trees and grass began to cover bare lots. More and more streets were scraped and graded on the sandy mesa.

Paradoxically, the Great Depression accelerated this expansion in the Near Heights and hastened the realignment of the city's axis to the east. Official New Mexico road maps in the early 1930s show U.S. Highway 66 running west from the Texas line to Santa Rosa, north from Santa Rosa to Romero, near Las Vegas, and then with U.S. Highway 85 south through Santa Fe to Albuquerque and Los Lunas before finally heading west toward Grants. Federal highway money soon supported the construction of a more direct route for U.S. 66 straight from Santa Rosa to Albuquerque and down Central Avenue. Central Avenue was soon paved all the way from downtown to the new WPA-built State Fairgrounds east of San Pedro. More importantly, massive federal work-relief programs during the mid-1930s underwrote the rapid extension of sewer and water lines, curbs, gutters, sidewalks, and streets in the areas surrounding the University. Federal work-relief funds also subsidized the expansion of schools and parks in the area. Meanwhile the federal government helped finance the construction of Bandelier Elementary School, Jefferson Junior High, and major additions to Monte Vista Elementary as well as the erection of Scholes hall, Zimmerman Library, a new student union building and several dorms at UNM. In 1936, the WPA also provided funds for the building of Fire Station Number Three (the Monte Vista Fire Station) at 3201 East Central, thereby reducing insurance rates in the immediate area by 43%.

|

The Depression also gave Albuquerque its Veterans Administration Hospital. A streetscape of trees was planted to create a path to the hospital that extended from Campus Drive at the University east to Carlisle, then across Central and south on Ridgecrest. The remnants of this streetscape are a defining characteristic of the adjacent Southeast Heights neighborhoods.

As a final inducement to revive the mordant construction industry by encouraging new house purchases, the newly created Federal Housing Administration provided federal insurance for liberal home mortgage loans. After a low of only 14 new housing starts in all of Albuquerque in 1934, house construction jumped to 353 by 1939 and topped the million-dollar mark for the first time in the city's history. By 1937 developer Charles McDuffie, the Dale Bellamah of his day, was finishing one house per week in the College View Addition east and north of Monte Vista. In the previous two years, McDuffie's addition alone had accounted for more than one-third of the city's entire residential construction. Other promoters would soon follow his example in the Near Heights, taking advantage of the infrastructure already in place.

After the interruption of World War II, of course, the Near Heights along with the rest of Albuquerque experienced an even greater expansion. By 1950, the city's population had almost tripled that of 1940, and nearly half of the new boom town lived in the new housing near the University. The growth of Kirtland Field, Sandia Laboratories, and related defense activity had launched the phenomenal suburban growth that persisted into the 1980s.

|

In the first decade after the war's end, several additions to the built environment near the University presaged both the maturity of the neighborhoods in the area and the rapid dispersal of population even further east that would characterize the next quarter-century. There was a wholesale erection of new churches in the Near Heights shortly after the war. By the end of the fifties, almost twenty churches of practically every faith stood in the neighborhoods near UNM, tangible evidence of new population shifts from the downtown area and testaments to a new sense of community stability and residential development.

A second type of new construction was less a symbol of maturity than a portent of the future. In 1948 the Nob Hill shopping center opened at Carlisle and Central, the first major commercial concentration outside the downtown, which acknowledged the importance of the automobile by providing site-contained, off-street parking. A short time later, the city's first branch bank, an extension of the First National Bank, opened its doors at Central and Richmond. Like the churches, these new additions seemed to be symbolic evidence of demographic change and a new urban geography. Along with the University and the State Fairgrounds, these commercial ventures reinforced the east-west axis of Central as Albuquerque's foremost commercial strip--a distinction that would remain until the construction of the Winrock and Coronado regional malls in the early 1960s and the completion of the Interstate network in 1966.

The built environment of the Near Heights has, of course, continued to change, not always for the better. The demands of the automobile in our increasingly decentralized city, for example, radically altered the cohesion of older neighborhoods. Interstate 25 cut through the western sector of the Terrace Addition, visually and spatially isolating it from downtown and consuming several blocks of its homes. Similarly, University Avenue and Lomas were realigned and widened, destroying whole blocks of houses on University. In addition, Lead and Coal Avenues became one-way, east-west streets and in the process, discouraged flow through north-south neighborhoods. Local institutions, such as the UNM, Albuquerque Technical-Vocational Institute (T-VI), and Presbyterian Hospital developed their own logic of growth in those years of rapid expansion. As "Pres" became a mega-hospital, its demand for new buildings and enlarged parking facilities meant razing blocks of surrounding residences, further eroding the beleaguered Silver Hill neighborhood. The rapid growth of T-VI also helped increase congestion in the Terrace addition, where many homes were now 40 to 50 years old in a city that valued newness.

And UNM, beneficiary of the GI Bill, federal development money, and the rapid postwar expansion of higher education, loosed an army of transient, highly mobile, house-hunting students into the aging University Heights area south of Central. The residential successes of the 1930s and 1940s were increasingly vulnerable in the 1960s and 1970s as some of the older neighborhoods, particularly south of Central and west of Girard, sought to cope with new social and economic pressures.

The newer Trumbull and La Mesa neighborhoods east of the Fairgrounds were heavily influenced by a zoning pattern in the 1950s that assumed future apartment development near Kirtland Air Force Base. The rationale for vast areas of high-density housing was the area's proximity to major employment centers. The zoning contributed to a proliferation of individually owned, four-unit apartments with inadequate consideration of parking, landscaping, or management. By the early 1980s the social and aesthetic problems inherent in this development pattern caused the established neighborhoods nearby to push for rezoning, city amenities, and city services to meet the needs of a dense and highly mobile population.

|

The Near Heights is a rich and varied environment distinguished by a mixture of land uses, ages, and ethnic groups. Its many special features and urban amenities within walking distance make the area a highly desirable place to live. In recent years the value of the Near Heights has become more apparent to city and institutional leaders, and local residents have discovered new means to stabilize and renew their communities. Benign neglect of public and institutional officials has begun to give way to a new accounting. Neighborhood associations and the city's Office of Community Development have begun to safeguard the many assets of the area's built environment. As they do so, even trouble spots like Central Avenue, a chronic magnet for transients, drug dealers, and the like, have begun to experience renewal. Small businesses--neighborhood pharmacies, restaurants, bookstores--are showing signs of flourishing again throughout the area.

The renovation of the Nob Hill shopping center, for example, has renewed commercial vitality along Central Avenue from UNM nearly to San Mateo. Nob Hill's proximity to the university, the overall residential strength of the area, and the demand of Albuquerque's growing population for specialty shops and restaurants have all contributed to the economic revival of the area. The streetscapes on San Mateo Boulevard and East Central are examples of recent public investment that stimulates and reinforces commercial revitalization in the community.

|

The stable residential neighborhoods of the Near Heights contribute to the vitality of the community. There are still problem pockets of decaying rental properties that neighborhood associations are striving to redress. But elsewhere the Near Heights neighborhoods remain strong. There is an economic and social diversity that is perhaps both a result and a reflection of the diversity of housing styles and construction in the second-and third-generation neighborhoods. Silver Hills, Spruce Park, Monte Vista, and other older areas were, for the most part, not tract-house suburbs. Variety of styles and solid craftsmanship increasingly appeal to many seeking homes in the area.

Streets in the Near Heights are lined with mature trees and established lawns, and sidewalks are often set back from curbs, encouraging pedestrian use and human interchange. There is in addition a sense of intimacy and human scale in many of the Near Heights neighborhoods. Few towering commercial buildings or massive apartment houses dwarf these residential neighbors. The multistory structures that do exist--churches, schools, hospitals--tend to anchor adjacent neighborhoods and define their perimeters. In addition, these buildings often serve cultural and social ends. Schools, especially, often serve as community centers. And UNM not only provides relatively easy access to a variety of cultural opportunities for nearby residents, it also offers significant expanses of open space for physical and other kinds of recreation.

|

Other institutions that anchor the community continue to thrive, sometimes with mixed effects on the neighborhood. Albuquerque International Airport is convenient to the Near Heights. The impact of air traffic on nearby neighborhoods has been hotly debated in public forums on future runway expansions. Presbyterian Hospital, Lovelace Medical Center, and the State Fairgrounds have all undergone extensive renovation and upgrading recently, which secures their place in the community. But along with the convenience associated with their jobs and services comes a need for communication between with their neighbors and mitigation of the impacts of regional centers on residential areas.

For over half a century the Near Heights was a key part of Albuquerque's dynamic expansion. Now, as growth accelerates and broadens in all sectors, many residents wish to preserve and nurture the values inherent in the built environment of the Near Heights as a legacy for the city's future.

(Up to Section II, Back to North Valley, On to Mid-Heights)