In

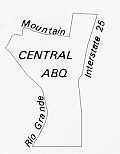

the few square miles between the river, the freeways, and Bridge Street lies

the "melting pot" of Albuquerque, although "robust stew"

is a more apt description. Here is the city's oldest building, San Felipe Church,

and the Botanical Gardens large, ranch-style homes and old three-room adobes,

lumber processing factories four blocks from the Albuquerque Museum, the city's

oldest park, and the Biological Park. Two-hundred-year-old barrios (neighborhoods)

stand next to solid, turn-of-the-century Anglo neighborhoods that, in turn,

abut modern apartment buildings.

In

the few square miles between the river, the freeways, and Bridge Street lies

the "melting pot" of Albuquerque, although "robust stew"

is a more apt description. Here is the city's oldest building, San Felipe Church,

and the Botanical Gardens large, ranch-style homes and old three-room adobes,

lumber processing factories four blocks from the Albuquerque Museum, the city's

oldest park, and the Biological Park. Two-hundred-year-old barrios (neighborhoods)

stand next to solid, turn-of-the-century Anglo neighborhoods that, in turn,

abut modern apartment buildings.

Downtown is surrounded by ten distinctive neighborhoods: Old Town, the Downtown Neighborhoods Area, Sawmill/Wells Park, McClellan Park, Martineztown, Huning Highlands, South Broadway, Barelas, the Raynolds Addition, and Huning Castle/Country Club. Each appeared on the stage of the city's history at its appointed time; their homes and stores still embody the hopes and dreams of decades, even centuries ago.

|

Oldest of them all is Old Town--originally the Villa de San Felipe de Neri de Alburquerque - where the city was founded in 1706 on a slight prominence on the flood plain of the Rio Grande near the Bosque Grande de Doña Luisa. Nothing is left from the Villa's early years; even the old 1796 San Felipe Church is a replacement of the original church. San Felipe still faces the plaza and still stands in the center of a cluster of low adobe buildings. These buildings now mostly house shops and restaurants rather than the residents of the Villa, but their relationship to the church, the plaza, and the narrow streets is virtually unchanged. Old Albuquerque took on new life with the coming of the railroad, and many buildings built after 1880 still stand. Unfortunately, the businessmen who built their stores, banks, and hotels so optimistically around the plaza soon moved to the bustling new railroad town two miles to the east. Old Albuquerque was left alone to quietly enjoy its old age. But during the 1930s, it was discovered by artists and writers, and the buildings around the plaza were turned into gift shops, restaurants, apartments, and artists' studios.

As happened in the quaint historic sections of so many American cities, Old Town soon became a tourist attraction; its historic architecture is now protected by a design review board. So it remains today, joined by museums, a large hotel and a popular new park. Large new retail developments have joined the old buildings, but the venerable San Felipe Church still remains the heart of its parish and the spiritual center for many descendants of the early Albuquerque settlers.

For

over a century, the Villa was the only village between the north valley plaza

of Duranes and, on the south, the land grant villages of Atrisco west of the

river and Peralta on the east side. Around 1825, a local rancher named Antonio

Sandoval, who owned many acres south of the Villa, dug an extension of the old

Griegos/Candelaria Ditch across the valley and south along the sand hills at

the valley edge to bring water to the fields below the Villa. More farmers moved

in, and soon a small village was formed. They called it Barelas, after the largest

family in the area. Barelas soon had its own church and graveyard, and spread

along the road south from the Villa that skirted the wide marshes along the

river. The old Barelas Road is still visible as it crosses from northwest to

southeast the grid-patterned streets established after the arrival of the railroad

in 1880.

For

over a century, the Villa was the only village between the north valley plaza

of Duranes and, on the south, the land grant villages of Atrisco west of the

river and Peralta on the east side. Around 1825, a local rancher named Antonio

Sandoval, who owned many acres south of the Villa, dug an extension of the old

Griegos/Candelaria Ditch across the valley and south along the sand hills at

the valley edge to bring water to the fields below the Villa. More farmers moved

in, and soon a small village was formed. They called it Barelas, after the largest

family in the area. Barelas soon had its own church and graveyard, and spread

along the road south from the Villa that skirted the wide marshes along the

river. The old Barelas Road is still visible as it crosses from northwest to

southeast the grid-patterned streets established after the arrival of the railroad

in 1880.

This momentous event changed more than the road pattern in Barelas, because the railroad located its offices and shops just to the east of the small settlement. New subdivisions sprang up to house the hundreds who came to work for the railroad from all over New Mexico and as far away as Germany. To this day Barelas displays two distinct types of homes: the adobes of the early Hispanic settlers and the brick and frame homes built by the newcomers. The railroad shops and the railroad whistle dominated the lives of Barelas residents for decades. As people began to travel and ship by air and automobile, the number of railroad jobs declined and so did Barelas. It is, however, still home to fiercely loyal residents. In 1995 new efforts were made to revitalize South Fourth Street, once the main road south, part of the fabled Pan American Highway.

|

Another old neighborhood that sparks a fierce loyalty in its residents is Santa Barbara/ Martineztown, which lies northeast of downtown. The neighborhood is really three distinct communities, and residents often act together to accomplish neighborhood goals. South of Lomas Boulevard nearly every building is new, a product of intensive community planning and the generous federal housing subsidies of the 1970s. Old residents live in the new apartments and duplexes; other new townhouses have been bought by down-town workers who appreciate their nearness to the city center. North of Lomas Boulevard are the winding streets and small, thick-walled adobes of the mid-nineteenth century settlement that is the core of Santa Barbara/Martineztown. Here also stand two important churches in the history of the community--the second United Presbyterian Church at 812 Edith NE, which was founded in 1889, and, high on the sand hills several blocks to the north, the 1916 Catholic Church of San Ignacio. Between these are small stores and a few remnants of the dance halls that once lined the intersection of Edith and Mountain Road. Just north of San Ignacio Church is the renovated, historic Santa Barbara School. The school building now contains apartments for seniors, city offices, and a photographic history of the community.

Directly south of South Martineztown is Huning's Highlands Addition, usually called Huning Highlands. This was the city's first subdivision, platted the same month as the coming of the railroad. Its developer was Franz Huning, who had worked hard to bring the railroad to Albuquerque. Here the store owners--like Mr. Learnard, who owned the music store, and Mr. Whitney, who owned the hardware store--and the teachers and the doctors of the new town made their homes. As more and more frame and brick Queen Anne style homes, some modest and some elaborate, were built, Huning Highlands came to resemble a quiet and settled Midwestern town. Residents had only to walk a short quarter-mile across the railroad tracks to buy their groceries, straw hats or a hammer, or to attend a performance of "The Pirates of Penance" at the Grant Opera House at Third and Railroad Avenue (renamed Central Avenue in 1907).

|

The Highlands began to lose its popularity as newer housing was built on the mesa after 1920, but it retained its respectability as a neighborhood that welcomed the many tubercular patients who flocked to`Albuquerque to "chase the cure." World War II created such a demand for housing that many of the larger homes in the area were divided into apartments and the smaller houses were bought for profitable rental properties. Since the energy crisis of the 1970s created a demand for close-in housing, the neighborhood has begun to come back. This renaissance has been bolstered by a renewed interest in Albuquerque's older buildings; the area was named a national historic district in 1979 and a city historic overlay zone in 1981.

Just south of Huning Highlands lies the South Broadway neighborhood. South Broadway has three distinct sub-neighborhoods: San José, Eugene Field, and John Marshall. The two last are named for their elementary schools; the reverse is true for San José, which gave its name to its school. San José, at the south end of South Broadway, is an early 19th-century settlement and was the home of Antonio Sandoval, the man who provided the Barelas Ditch. Its ties with Barelas are many. The communities were split by the railroad, but their similar histories bind them together.

At the northern end of South Broadway is the Eugene Field neighborhood, a post-railroad subdivision similar in architectural and residential character to Huning Highlands. This neighborhood is slowly being rehabilitated as housing near downtown becomes more desirable. Between Eugene Field and San José lies the John Marshall neighborhood, part of the large 1888 Eastern Addition, which offered inexpensive housing for railroad workers. Segregationist attitudes and economic constraints created a predominantly black neighborhood here in the 1920s and 1930s.

|

Flanking the downtown on the west is another railroad-era, middle-class neighborhood, the Downtown Neighborhoods area. Development gradually grew into the center of the area from the city limit on the west, from the new town on the east, and north from Railroad Avenue, which connected the old and new towns. Building increased after the completion of the Belen Cutoff, a section of track that connected the railroad systems of Texas with the rail lines going west to California through New Mexico. Two- and three-story, solid houses of brick and stone began to appear along Eleventh, Twelfth, and Thirteenth Streets between Central Avenue and Lomas Boulevard, then New York Avenue. Prominent citizens such as the Rosenwalds, Berthold Spitz, Albert Grunsfeld (for whom Temple Albert was named), banker Mariano Otero, and educator Amado Chavez all lived in what was known then as the Fourth Ward. Under that name much of the area is listed as a historic district on the National Register of Historic Places and was designated a Historic Overlay Zone.

Like Huning Highlands, the Fourth Ward began to decline in popularity as newer and more up-to-date homes were built on the mesa. After World War II several of the large homes were used for group homes or halfway houses. An aroused neighborhood formed one of the city's earliest neighborhood associations and gradually began to change the area by obtaining more residential zoning, pressuring the city for services and a new park, and forming a neighborhood housing rehabilitation agency. Guided by the ever vigilant neighborhood association, the Downtown Neighborhoods area has again become a desirable place to live.

The Association area includes far more than the Fourth Ward District. Its boundaries also incorporate the area between Lomas and Mountain Road as far west as Nineteenth Street. This area contains the charming 1940s all-adobe subdivision built by long time local builder Leon Watson in the Chacon Addition and the two long parallel blocks of well-preserved, modest early 20th-century houses on Eighth and Forrester. Eighth Street/Forrester has also been designated a Historic Overlay Zone. Many of its homes, like those to the south, are being rehabilitated.

|

Everything north of Mountain Road was beyond the city limit in 1900. Here a giant sawmill was built in the early 1900s; its source of lumber the Zuni Mountains to the west. In the blocks around the sawmill, many workers built frame and/or adobe homes. Three small neighborhood grocery stores still stand unchanged in the neighborhood, although only one is now operating. Sawmill resembles Barelas both as a working-class neighborhood and as a mixture of Anglo and Hispanic building styles. And like Barelas, its history predates its major industry along Mountain Road, a historic route to the mountains from Old Albuquerque.

East of the Downtown Neighborhoods area, around the uniquely formal McClellan Park at Fourth and Slate, was once a thriving turn-of-the-century residential neighborhood. Its proximity to downtown and the railroad and its bisection by Fourth Street created an area ripe for commercial intrusion. Car-related businesses grew up on and near Fourth Street, and railroad-related warehousing went in near the tracks. Between these uses, both incompatible with residential use, the neighborhood had little hope of survival as a place to live. Division by the one-way streets serving the central business core further weakened it. In 1995 a federal courthouse was proposed to be sited on Lomas between Third and Fourth Streets. The few modest and charming older houses tucked away on First, Second, and Third streets might survive to be re-used as offices serving the courthouse.

After 1910 only one area bordering on downtown remained undeveloped; this was the swampy area that lay between the old Barelas Road and the river. A real estate company platted the Raynolds Addition between Eighth Street and the city limits (roughly at Seventeenth) in 1912. The area filled in slowly (probably because of the marshes) and now shows an intriguing combination of small houses built in the 1920s and Southwestern style apartment houses built in the late 1930s and 1940s.

Farther west lay the grounds of Castle Huning, an elaborate home built in 1883, marshlands, and a pig farm. In 1928 plans to drain the swamps were under way by the newly formed Middle Rio Grande Conservancy District when the land was bought from Franz Huning by A. R. Hebenstreit and Will Keleher. Huning had built his fabulous home on Central (then Railroad Avenue) at the northern edge of the swamps. The new addition was named the Huning Castle Addition in his honor. It was to be a prestige area and the few picturesque homes built there before the great stock market crash of 1929 certainly realized the developers' hopes. The Albuquerque Country Club moved to its current site the year the addition was platted, and all appeared to be going well until the depression brought construction almost to a halt. Most of the large and gracious homes that line the shady streets of what came to be known as the Country Club area appeared after World War II. The neighborhood has kept its upper middle-class character and many grandchildren of the original residents return to live there.

At

the center of this circle of varied neighborhoods lies its core, the New Albuquerque

of 1880. Downtown began as a cluster of frame and adobe buildings near the railroad

depot at First Street (then called Front Street) and Central Avenue (then called

Railroad Avenue). Albuquerque became the commercial and retail center of the

state by 1910 and Downtown was the place to go for nearly 50 years. Downtown's

center gradually moved west to Fourth and Central, the intersection of Route

66 and the Pan American Highway. Within a quarter mile were hotels, department

stores, restaurants, movie theaters (eight in 1944 for a town of about 50,000!),

banks and government offices. As residential subdivisions spread over the east

mesa after the World War II, the shopping and entertainment facilities followed

them. Downtown's dominance as the retail center of the city was ended when Winrock

and Coronado were built in the 1960s, north of the new east-west freeway. Urban

renewal programs from this period caused the removal of many of the small, intricate

buildings dating from the city's railroad era. A major loss was sustained when

the Santa Fe Railway demolished the Alvarado Hotel, the grand 1901 Fred Harvey

Hotel, which sprawled between First Street and the tracks south of Central.

Other significant buildings demolished by their owners in this period were the

unique Pueblo Deco Franciscan Hotel, the Victorian office, hotel, the store

block called the Korber Building, and the Ilfeld Warehouse, a barnlike, early

poured-concrete structure. Since 1980, Downtown has welcomed rehabilitated historic

buildings, as well as an expanded convention center and new hotels and office

buildings as it emerges from nearly three decades of decline.

At

the center of this circle of varied neighborhoods lies its core, the New Albuquerque

of 1880. Downtown began as a cluster of frame and adobe buildings near the railroad

depot at First Street (then called Front Street) and Central Avenue (then called

Railroad Avenue). Albuquerque became the commercial and retail center of the

state by 1910 and Downtown was the place to go for nearly 50 years. Downtown's

center gradually moved west to Fourth and Central, the intersection of Route

66 and the Pan American Highway. Within a quarter mile were hotels, department

stores, restaurants, movie theaters (eight in 1944 for a town of about 50,000!),

banks and government offices. As residential subdivisions spread over the east

mesa after the World War II, the shopping and entertainment facilities followed

them. Downtown's dominance as the retail center of the city was ended when Winrock

and Coronado were built in the 1960s, north of the new east-west freeway. Urban

renewal programs from this period caused the removal of many of the small, intricate

buildings dating from the city's railroad era. A major loss was sustained when

the Santa Fe Railway demolished the Alvarado Hotel, the grand 1901 Fred Harvey

Hotel, which sprawled between First Street and the tracks south of Central.

Other significant buildings demolished by their owners in this period were the

unique Pueblo Deco Franciscan Hotel, the Victorian office, hotel, the store

block called the Korber Building, and the Ilfeld Warehouse, a barnlike, early

poured-concrete structure. Since 1980, Downtown has welcomed rehabilitated historic

buildings, as well as an expanded convention center and new hotels and office

buildings as it emerges from nearly three decades of decline.

The recent resurgence of the neighborhoods as desirable and viable places to live supports and reflects the current revitalization of Downtown. Their vitality and variety matches the diversity and new growth in the business core. Unlike downtowns in so many American cities, Albuquerque's center has the good fortune to be surrounded by diverse, active, and healthy neighborhoods.

(Up to Section II, Back to South Valley, On to North Valley)