The

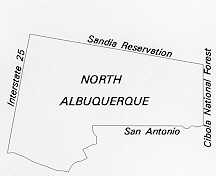

North Albuquerque community is located north of Bear Canyon Arroyo and extends

to the Sandia Reservation boundary and from Sandia Heights to Interstate 25.

Most of its neighborhoods are new and reflect the city's modern development

standards--landscaped commercial nodes, large-scale apartment complexes, and

walled, single-family subdivisions.

The

North Albuquerque community is located north of Bear Canyon Arroyo and extends

to the Sandia Reservation boundary and from Sandia Heights to Interstate 25.

Most of its neighborhoods are new and reflect the city's modern development

standards--landscaped commercial nodes, large-scale apartment complexes, and

walled, single-family subdivisions.

Much of what is now North Albuquerque is built on the Elena Gallegos Land Grant. In 1891 Congress gave the Elena Gallegos, or Ranchos de Albuquerque, Grant to the heirs of Diego Montoya and Elena Gallegos. The Elena Gallegos Land Grant extends from the Rio Grande to the crest of the Sandias. When the original grant holders failed to pay required taxes, the Mutual Investment and Agency Company gained title to the eastern portion of the grant. Today the North Albuquerque community occupies much of this portion of the land grant. In the 1930's Norins Realty Company of California acquired 5,700 acres of the Elena Gallegos Land Grant. In 1931 Norins Realty platted North Albuquerque Acres into a grid of rectangular, one-acre lots and sold many of them by mail to individuals throughout the U.S.

|

Typical lots were 165 ft. by 264 ft. to the centerline of the road easement. Public road easements are 60 feet, so that lot sizes exclusive of road easements range from .73 acre for a corner lot to .89 acre for an interior lot. The platting ignored natural topography and drainage patterns, leaving some lots with eroding streets and little buildable area. A series of dams and diversions consolidated drainage-ways in most of the subdivision. In 1978 the city completed a plan for North Albuquerque Acres advocating public redevelopment assistance through the assembly and replatting of existing lots. However, comprehensive land assembly was never accomplished, and extensive development in the eastern part of the subdivision has locked in the grid-lot layout and street pattern. Subsequent planning efforts have focused on replatting small areas that can be assembled by private concerns.

At the western and southern edges of North Albuquerque Acres, replatting has been more successful. In some cases, such as Heritage Hills and Heritage East subdivisions, which were planned in 1976 and 1981, large tracts were held in single ownership. In other neighborhoods, notably Nor Este Estates, Vinyard Estates and other subdivisions surrounding La Cueva High School, lots were purchased and assembled into tracts large enough for redevelopment. The trend toward assembly and redevelopment by private concerns is continuing, but it is a slow process and results in high finished-lot costs.

In 1934 Albert Simms bought most of what was left of the Mutual Investment Company's portion of the grant and left much of it to Albuquerque Academy when he died. Over the years parts of the academy land holdings have been sold to fund an endowment. Originally Simms' property extended to the crest of the Sandias. That mountain land was included in a three-way trade between the academy, the U.S. Forest Service, and the City of Albuquerque. The trade was important to the preservation of open space in the Sandia foothills. The final result of the trade added the mountains to the Cibola National Forest, created a land trust to help fund the fledgling Albuquerque Open Space Program, and provided revenues to Albuquerque Academy. Simms Park and the Elena Gallegos Picnic Area located within it are a showpiece of the city's open space program. The entire open-space tract occupies approximately 640 acres; 11 acres of which is the picnic area.

|

The Sandia Peak Ski Area opened in 1937. Access to the ski area was a narrow, winding road up the west side of the mountain. Two local developers, Bob Nordhaus and Ben Abruzzo, envisioned a tramway up the mountain to connect to Sandia Peak from the east side. Construction began in 1964, and what would later be billed as the "World's Longest Aerial Tramway" opened in May 1966. The two men purchased land at the base of the tram for the terminal and parking lot along with some additional land that was then developed and sold as residential lots. Between 1965 and 1975 Nordhaus and Abruzzo bought 1,500 acres of the Sandia foothills, land that has been developed slowly over the years.

Sandia Heights was the first Albuquerque subdivision to include water conservation in its plans, and the natural landscape was an integral part of the subdivision design. The practical reasons for the early adoption of xeriscape and environmentally sensitive development are being strongly advocated today. Water conservation has been essential to the success of the subdivision, which operates its own water system.

|

Denser populations are clustered near Tramway Boulevard, and most of the lots east of Tramway are about 3/4 acre. Large lots and minimal grading meant that the natural drainage pattern of the foothills need not be altered--a cost-effective alternative to the channelization and concrete lining of arroyos being done in other parts of Albuquerque.

The early intent of the developers was that houses blend with the natural environment. Minimal changes to the natural landscape had an additional benefit in a community of custom homes where lots have remained vacant for a number of years. Vacant lots blend with the rest of the neighborhood, leaving no obvious "holes" in the subdivision. Homeowners in Sandia Heights are required to leave native landscaping in place. For example, a formal lawn of no more than 500 square feet is allowed within a walled garden. Muted colors and natural materials are typical, although some newer homes reflect the "Scottsdale" design of other urban neighborhoods.

In 1982 the Academy/Tramway/Eubank Sector Development Plan was completed for the area now known as Tanoan. This area includes 1,321 acres of the academy lands purchased for private development. Major drainage-ways through this area were developed as a golf course and country club.

|

A 307-acre parcel of land was acquired in the early 1960s by the city through a land bank agreement with what was then Albuquerque Academy for Boys. Thus the city obtained a regional park in the area bounded by San Mateo, Eubank, the Elena Gallegos grant line, and San Antonio Boulevard. The academy deeded Arroyo del Oso Park to the city, and as the academy sold off land in this area for residential development, subdividers paid into a fund for park development instead of dedicating park land. The city paid the academy for the park from the proceeds of these cash payments.

The Arroyo del Oso Park is a good example of multiple public uses in one location. It includes a golf course, tennis courts, and soccer complex. Later developments expanded its focus as a recreational complex. Other public facilities within the property include Fire Station #15 and the John Carillo Memorial Police Substation. Next to the police substation is the Xeriscape Demonstration Garden, one of the best examples in the city of the potential of xeric landscapes.

At the time it was developed, Arroyo del Oso Park stood at the northern edge of the city, and no one anticipated the development boom that would occur further north of it. The Bear Canyon Arroyo runs through the property and serves as a major drainage, integrated with the park's recreational purpose. The park's major drawback is that it blocks all north/south roadway access for two miles between San Mateo and Wyoming Boulevards. The dam in the park is located near the western end of the golf course and effectively blocks any extension of an arterial street through the park. Nowadays the city is more careful to assure access through other linear open spaces as a result of the lessons learned from Arroyo del Oso Park.

|

There has been a growing awareness of the environmental consequences of development patterns in the Northeast Heights. Early subdivision design was based on house-building patterns in the traditional, rectangular survey system and ignored topography and drainage patterns. In Near Albuquerque and in parts of the Mid-Heights, arroyos were obliterated during development, with all storm drainage placed in the streets. This pattern has made necessary the extensive retrofitting of underground storm drains. The layout of North Albuquerque Acres also ignored drainage patterns, but the street and drainage systems in newer North Albuquerque subdivisions are more sensitive to topography and natural drainage patterns.

(Up to Section II, Back to Mid-Heights, On to East Gateway)